12 - 48 Months

Ways to raise a bilingual child

“There’s a bilingual advantage that we see in the research, and just practically speaking, there are cognitive, social, cultural and economic benefits to being bilingual.”

Dr. Veronica Fernandez, Psychologist with a specialty in bilingualism

Toddlers love words. This enthusiasm helps them grow their spoken words from just a few at age one, to 1,000 or even 2,000 by age three. Given how receptive young children are to new sounds and ways to use them, it is not surprising that toddlers can pick up second languages easily. Research also suggests that brain connections multiply when babies are exposed to new languages. Parents have caught on, and demand for bilingual products and preschools is at an all-time high.

While experts agree on the benefits of exposing kids to multiple languages, the best means of doing so is up for debate. On today’s episode, Host Jessica Rolph is joined by Dr. Veronica Fernandez, a developmental and child psychologist, with tips on how to best approach bilingualism in the home.

Key Takeaways:

[1:35] Veronica talks about the benefits of raising a bilingual child and shares the reasons why she is choosing to raise her daughter, Isla, with two languages.

[3:02] How can parents who only speak one language at home best lay a strong foundation for bilingualism at home?

[5:05] Veronica discusses the advantages and disadvantages of various approaches to bilingualism.

[6:57] Veronica speaks about the challenges of raising Isla as bilingual.

[8:00] How important is immersion? Do kids benefit from occasional exposure to a second language, or do they need to have some component of an immersive experience?

[8:50] Veronica debunks some myths about bilingualism, including the unfounded concern that learning another language may cause your child to have a speech delay.

[11:13] What if your child is using two languages within one sentence?

[12:25] What about those talking books and toys that switch from one language to another? How effective are they?

[14:21] Toddlers generally experience a language explosion around 18 months to 2 years; should parents expect the same of a bilingual baby?

[15:07] Should a parent drop a language if a child has a perceived delay?

[16:01] Is there an optimal age to introduce a second language?

[16:48] Veronica offers a few tools to teach the target language.

[18:01] If a child is reluctant to speak the second language, what can be done to encourage them?

[19:35] Veronica shares tips for parents who are monolingual and want to introduce their babies to another language, as well as for bilingual parents who are also on the journey to bilingualism with their children.

[21:40] Jessica reviews the highlights of her conversation with Veronica.

Script:

Advantages of raising a bilingual child

Jessica: Hello, Veronica.

Veronica: Hi, Jessica. Thank you for having me.

Jessica: It’s so great to have you with us. So let’s just get right into it and start with an overview of the benefits of raising a bilingual child. What are some reasons why you’re choosing to raise your daughter, Isla, with two languages?

Veronica: I think for me and most parents who are making the effort to expose their child to more than one language, it’s really about setting them up for success. There’s a bilingual advantage that we see in the research and just practically speaking, there are cognitive, social, cultural and economic benefits to being bilingual. We know that learning more than one language improves brain architecture and frontal lobe functioning, and there’s also this cultural advantage. So when you’re teaching your child a language that connects with your culture, which in my case is Spanish, my family is Cuban, it helps to strengthen that connection with your family heritage. There’s actually a quote on the Lovevery page that really resonated with me. It says, “Our most treasured family heirloom is our sweet family memories that we pass down to our children.” And I think language can be so powerful in connecting our children to our family history. So for me, it was really about the cognitive advantage and also that cultural connection to my family.

Approaches to teaching a second language

Jessica: And I’ve read that bilingual children have even a more flexible brain system, so I’m totally sold on the benefits. And I was sold on the benefits when I had my first, but I had so much trouble figuring out how to introduce a second language because for me, I only speak one language at home, and so I just didn’t know how I could make it happen. So how can parents in this situation best lay a strong foundation for bilingualism at home?

Veronica: I’d say to sit and reflect about your goals and also consider what’s feasible. Consistency is important to learning a language, so think about what you can realistically commit to, and then have a plan. For some families, strict structure works. You may decide that you want to use something like OPOL, which is one parent one language, that I can unpack a little bit later on, or speak English on even days and another language on odd days. For others, that’s going to feel too restrictive and you want to engage more naturally with a language, or somewhere in between, which is what I personally do. We don’t have a schedule, but I try to alternate. So for example, I might read a book to Isla in English in the morning, and then I keep that in the back of my mind, so when I’m reading that book to her again later that day or another day, I will read it to her in Spanish. Same for routines. I might spark a conversation with her during breakfast in Spanish, and then I make an effort to speak to her in English during lunch. So that alternating and just being intentional about using the languages during these meaningful interactions that are just part of her day is a way to do it that takes a little bit of pressure off.

So families shouldn’t feel like they’re teachers and they have to have a lesson plan and have a very prescribed way of teaching language, rather just engaging in these meaningful interactions through the context of routines and meals and play is really a way to do it where some of that pressure could be taken off.

One parent one language method

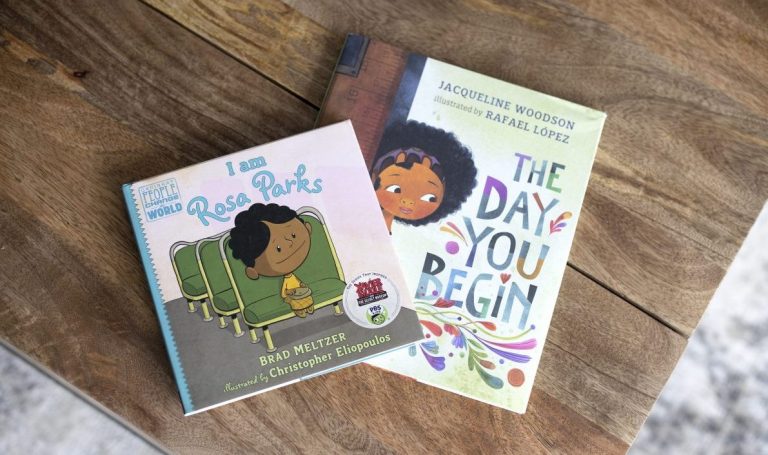

Jessica: Yeah, I felt like books were the most accessible for me. We’re going to be launching books in Spanish soon for Lovevery, and so excited to provide access. And for me, reading books in French or Spanish or other languages was a much easier way for me to access bilingualism or exposure to another language to my babies. So I love that you mentioned that. Can you talk a little bit more about what you said about one parent one language? There’s also other approaches, like one caregiver, one language, minority language at home. There’s all these different kind of approaches. Can you talk a little bit about this, and the advantages and disadvantages of each?

Veronica: Sure. One parent one language or one caregiver one language is essentially where one person only speaks in one language to and around the child. So for example, if you have a dynamic in your family where one of you only speaks English and your partner may speak English and Arabic, then you would only speak English to your child and your partner would only speak Arabic to your child. Or if you have a caregiver, such as a nanny, who helps out with your child and that nanny only speaks Farsi, then that caregiver would only speak Farsi to the child, and then you at home would only speak Spanish or English to your child at home. Same thing with a group care context. If the caregiver in a group care context only speaks Spanish, you would speak English at home and they would speak Spanish in the caregiving setting.

And there’s research on OPOL, it is effective, but it doesn’t necessarily fit everyone’s lifestyle. It is a big commitment to stick to one language and can sometimes strain communications between partners. So if I’m only speaking to my child in Spanish and my partner’s only speaking in Spanish, that sometimes can strain our communication, which is also important for children to sort of hear that model of communication, that serve and return in conversations that other folks are having. So it’s one way to support your child, but it’s not the only way. You don’t have to implement an approach that strict. It’s important to, like I said, do whatever works for your family dynamic and think about what’s feasible. And if you don’t speak another language, as you mentioned that you are a monolingual English speaker, you can even decide to learn a language alongside your child, or you can bring other folks into the language journey with your child and have some of that shared responsibility.

Challenges of bilingual education

Jessica: And so I love how you brought to life some of the challenges and the nuances of these different approaches. Did you have any particular challenges when raising Isla as bilingual, so far?

Veronica: Yeah, so I think, as everyone else, we have ideas of the type of parent we’re going to be, and then we are parents and our realities are sometimes slightly different than the idealistic dream that we had in our mind. So I will say that Isla’s exposure to Spanish is less than what I would have liked, but I am keeping it up with my family and with her. So I think one of my challenges is that we wanted to do it a lot more intentionally. My mom, for example, Spanish is her first language, it’s her dominant language, but because my interactions with Isla tend to be in English, my mom tends to default into English with her as well. So it’s one of those things where I’ve encouraged her like, “No, only speak to her in Spanish so that she gets to practice Spanish with you and she sort of sees you as a Spanish language model.” So it’s just challenging to stick to an approach. And I mentioned before that alternating reading a book in one language and another, but it’s not something where I have a spreadsheet and I’m keeping tabs, so sometimes I don’t quite engage that intentionally in switching to the languages when I’m having an interaction.

But yeah, I would say that I think the biggest challenge is that I’m speaking less Spanish to her than I would like, so her bilingualism isn’t quite balanced. I would say that English is dominant for her, and she’s speaking some Spanish and she’s fluent, but not quite as much as in English.

Benefits of language immersion

Jessica: Yeah, thank you for sharing that. It’s always helpful to hear the nuances of what it’s really like. And so it gets me to my next question, which is, how important is immersion? Do kids really benefit from occasional exposure to a second language or do they need to have some component of an immersive experience?

Veronica: So I would say that there’s going to be some benefit to some exposure, and there’s going to be a lot of benefit to more exposure. They’re both on a continuum. So however much exposure the child has is also going to correlate with the benefit that the child is experiencing from the language immersion. So, absolutely, knowing a few words can help you when you’re traveling, when you’re connecting with your peer, ordering something at a restaurant, but the more fluent a child is, the greater advantage that the child is going to have in their frontal lobe functioning, in their brain flexibility, and in that brain architecture.

Myths and misconceptions about second language learning

Jessica: So I wanted to also go over some myths with bilingualism, and one of the myths is that learning another language will actually cause your child to have a speech delay. Can you share more about this?

Veronica: Absolutely. There’s actually no evidence that learning a second language is going to contribute to or cause a speech delay. We do sometimes find that bilingual children say their first words slightly later than monolingual English-speaking children, but they typically still stay within the normal age range, between eight to 15 months. And when they do start talking and putting words together into phrases and sentences, they tend to develop grammar along the same patterns and timelines as monolingual children.

When you think about language exposure, the output that you’re going to get from that is not just the child speaking. That’s not the only metric for measuring the child’s benefit and success. So if we unpack the benefits that children who are bilingual have, we see children who perform better than monolingual children on executive functioning tasks. So things like working memory, cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control. So it’s not always going to be something verbal that we see that’s tangible, that’s indicating the benefit that they’re experiencing through their bilingual exposure. They show faster processing speed and problem solving, and we see this really early on.

So I’ll give you a quick example. There’s an assessment of infant and toddler development, and for one item, the assessor places an object or a toy in a clear container and the opening is facing the child. So most babies, monolingual, bilingual kids, they reach in, grab a toy and that’s a pretty simple task. Then without the child noticing, the assessor turns the opening away and monolingual babies, those who speak or are exposed to only one language, tend to spend a lot more time trying unsuccessfully to get the object from the side that they previously tried, because that’s what worked for them. Whereas children who are bilingual, in that they speak or are exposed to more than one language, because their babies they may not be verbal yet, at first they try the side that was successful, but when their hand hits the container, they more quickly start to explore the other side of the container. They reach to the open end, get the toy.

And that’s just one example very early on of a cognitive advantage that doesn’t involve their verbal abilities and their speaking abilities, but these babies are better able to problem-solve, and they do so a lot more quickly.

Translanguaging and code-switching

Jessica: I had never heard of that study before. That is so interesting. Another myth, so now that we’re going and breaking down the myths, is that what if your child is verbal and they’re using two languages just within one sentence? So I think a lot of parents can think, “Oh, are they getting confused by the bilingual environment?”

Veronica: In fact, when they code-switch or they engage in what research is calling translanguaging, in Spanish and English we call it Spanglish, it’s a combination of Spanish and English. When children code-switch, that doesn’t mean they’re confused. It may be because there’s a gap in the knowledge of a particular word or because they understand that there isn’t an exact equivalent to a particular word in the other language. Or it may be because there’s emotional connection to that language. For example, I often say that I feel in Spanish. I speak in English and I feel in Spanish. So sometimes when I’m speaking in English, if I’m referring to an emotion word, I may name the emotion in Spanish. And it’s not because I have a deficit in English or I don’t know the word, but there’s just an ease of that connection in terms of my processing, and my schema in my brain for emotion functions more rapidly in Spanish. So these children may be doing that for multiple reasons, but just because they’re using more than one language… And that’s why I try not to say they’re mixing languages, I say code-switching or say translanguaging, so that parents understand that there’s a term for this and it’s something that’s just a normal part of the language process and it doesn’t indicate any sense of confusion or deficit.

Jessica: So speaking of code-switching, what about those talking books and toys that switch from one language to another? How effective are they?

Veronica: So the research doesn’t demonstrate any benefit to those toys. And in fact, I have some concerns about toys that particularly allow the child to press a button and hear the word in English and then in another language, because there is a lot of evidence to not using back-to-back translations for the purposes of teaching the language. We sometimes refer to it as the airport effect. So if you’re at the airport, they make a lot of announcements, especially in an international airport, they make a lot of announcements in a lot of languages. If you have a dominant language, your ear is listening for the announcement in that dominant language. If you have a secondary language or even a third language that you know, you tend to not listen to those announcements because you’re waiting for the ones that make more sense to you, that is easier cognitively for you to process.

This is something that happens automatically in our brains. So when children are pressing buttons and they’re doing something very passive, when they’re interacting with toys, they tend to listen and process their dominant language more easily, and there isn’t a lot of attention paid to the other language. So it’s not an effective way of teaching language for that reason, and also because the most effective way to teach languages is in a natural context, so with sustained conversations, through interactions that have that natural serve and return, where there’s a back and forth and the response that they get is directly resonating with what they said, so what they’re producing and they’re going back and forth. And that human interaction is critical and most effective for language learning.

Bilingual language and developmental milestones

Jessica: Which makes so much sense because it’s that serve and return, that is just the foundation that we’ve learned is so meaningful, and so babies generally experience this language explosion, or I should really say toddlers, around 18 months to 2 years to 2 and a half, should parents expect the same of a bilingual baby?

Veronica: So they certainly should expect this explosion, but not necessarily with that same timing, and it’s also how we’re counting words, so for example, we have to think about their cumulative language, oftentimes, you may count how many words they know in English and say, ‘Well, I’m not going to count this other word, because it’s the same object that they’re naming in English and in their second language,’ and in fact, that does count as a separate skill and a separate word. Essentially, if it’s typical that a child knows and uses 50 words, count the words that they know across both languages, even if it’s for the same thing. And another thing that I mentioned before is that you may see it delay on the onset of talking, but once they do start talking, they catch up pretty quickly and are at the same pace as monolingual children.

Jessica: And so just to be sure, should a parent drop a language if a child has this delay that they’re perceived delay.

Veronica: So the research is pretty clear in that bilingualism doesn’t cause or contribute to a speech delay. I’ll say that 100 times if I have to when I speak with families, so I wouldn’t. What I would do is ease up on any pressure that the family is feeling or putting on the child, but continued exposure is good for the brain and language begets language. So the more exposure that they have, the more of those serve and return interactions, even if the child is not speaking, I still encourage the parent to model that speaking to the child where they’re looking at the child and waiting for a response, even if it’s a non-verbal response, it’s a smile, it’s maybe signing with their hands and then responding contingently to what the child is saying and engaging that back and forth is going to be helpful to the child.

When should I teach my child a second language?

Jessica: And then is there an optimal age to introduce a second language? Is there a right time when we should be thinking about this?

Veronica: So I always say that it’s never too early and it’s never too late, which I know sometimes is an unhelpful answer for families, but I say it’s never too early because starting early is best. The ideal language learning window is during the first few years of life, because this is when the most rapid period of brain development is happening. So when children are really young, their brains are really capable of learning languages, and that’s when learning languages is easiest, but it’s also never too late because if you start later with your child, it’s maybe going to be a little bit more challenging, but certainly not impossible. Older children and adults can still become fluent in a second language or beyond, and there are so many benefits to learning another language that I think it’s well worth the effort.

Tools and encouragement for bilingualism

Jessica: And so speaking of this effort, do you have any tools that you recommend to teach the target language?

Veronica: You know, I get this question all the time, and I always say, “No.” Nothing specific really, everyday life. Household objects, toys, books, so the same things that you already have are great ways to facilitate language learning within the context of play, within the context of… For example, you had a podcast series that talked a lot about house tours, going around with your child and just naming everything in your house, making them familiar with areas of the house while you’re cooking with your child, explaining what you’re doing in that language, if you know that language. Now, if you are not a speaker of that language, then of course you can bring in some things that are going to help facilitate that language learning, so things like music in the other language, audio books that you play could be beneficial to the child, but I’m not big on these picture cards. I often see families feeling like they have to create or buy 50 cards for the child to name and memorize, but I don’t really press from memorization, in terms of a cognitive priority. I advocate for functional language in everyday interactions that are meaningful to the child, so just talking about real stuff.

I had a funny interaction with a parent who said something like I said, “Use real stuff, their toys, their books, anything that you see on your walks when you’re inside the house or outside of the house, or while you’re riding in the car, and one of the parents said, Well, I don’t have whatever it is that she was trying to teach and my question was, Well why are you trying to teach it? And the child is never exposed to this object either in pictures or in real life, it’s just not something that’s going to be meaningful for the child, then I wouldn’t really prioritize that in terms of something to teach.

Jessica: That’s so helpful. And if a child is reluctant to speak the second language, what can be done to encourage them?

Veronica: So I always wonder when a family says that their child is reluctant, I wonder about whether there’s a lot of pressure being put on the language learning. So I would say that my biggest piece of advice is to approach language learning from a playful perspective, so just integrate it into the child’s life, it shouldn’t feel like it’s something that’s very didactic, that the parent is pushing, so if it’s just part of their daily interactions, I don’t tend to see that reluctance. It’s when children are being enrolled in French classes or being forced a little bit more, that there is more of that reluctance. We also see some of that reluctance when there’s a native language being spoken at home and children start school, and they’re interacting with their peers and teachers in English only, then you do tend to see a little bit of that reluctance to continue to speak the native language at home, so the advice that I give to families is, Don’t pressure the child to speak the language, but you continue speaking that language, so you continue to expose to that child, even if that child response to you in English every single time, you continue to speak your native language at home and interact with the child in that way.

So continue the exposure, but not pressuring the child to necessarily speak or respond in that language.

Jessica: Veronica, it’s been wonderful having you with us today, thank you so much for coming back again.

Veronica: Absolutely, any time. Always so fun.

Four episode takeaways for parents

Even though my children didn’t have a bilingual start, I find the families who do, so inspiring.

1. It’s never too late for second language learning

To get results, don’t feel like you have to implement a strict approach, like One Parent, one language: There is always some benefit to some exposure. Consider learning alongside your child. Books are a great place to start.

And while children are primed to learn languages before the age of 3, it’s never too late to re-invigorate your intention to bring a second language into the mix. Fluency does not need to be the goal.

2. Offer back-and-forth dialogue

Back to back translation, the kind you see in books that provide the text in both languages, is not particularly helpful. Children pay attention to the dominant language (as do adults) and tend to tune out the secondary language. Better to aim for sustained interactions that offer the back-and-forth dialogue that happens naturally in a conversation. Even if your child is not speaking, pause and allow them to respond non-verbally.

3. Meaningful interactions instead of memorization

Approach language learning from a playful perspective. If the language is part of the child’s daily interactions, there tends to be less reluctance from the child. Veronica recommends functional language that stems from meaningful interactions, rather than memorization of vocabulary. House tours are a great place to start.

4. Code switching is a normal part of the process

When children code switch (speaking Spanglish or Franglish, for example) it doesn’t mean they are confused. They might feel an emotional connection to a word in one particular language over the other. This is a normal part of the language process.

Continue to speak the target language even if your child is responding in the dominant language. Pressure to respond in a certain language can backfire.

You can find more tips on language development on the Lovevery blog at https://lovevery.com/.

Posted in: 12 - 48 Months, Child Development

Keep reading

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

Lovevery for Target

Experience our new Target stage-based play essentials, as well as familiar favorites like The Play Gym and The Block Set, straight from your local Target location.

12 - 48 Months

18 - 48 Months+

0 - 12 Months

8 ways to celebrate Earth Day as a family

Earth Day is a time to celebrate nature and the environment. Teach your children how to take care of the Earth with these fun activities, crafts, and books.

12 - 48 Months

Welcome spring with these colorful, toddler-friendly DIYs

Incorporating color into these fun DIY activities stimulates your toddler's senses and deepens their learning.

12 - 48 Months

13 - 15 Months

0 - 12 Months

Celebrating Black History Month with babies and young children

Children of all races are never too young to take part in Black History Month. Here are ideas on how celebrate with your child, along with a list of books that center Black people and culture.

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

What are Montessori toys?

Some toys have characteristics that are aligned with Montessori principles. Learn what they are, why they can benefit your child, and how to introduce them.

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

You can’t balance work and parenting during Covid. That’s OK.

As we continue to adjust to new normals, some things have stayed the same: working while caring for young children during a pandemic is really hard. Here are a few ways to ease the burden.

12 - 48 Months

4 activities that expose your toddler to the wonder of color

Color brings fresh interest to STEM and art projects for your toddler. Here are 4 easy ones that use food coloring.

12 - 48 Months

6 outdoor activities you can bring inside when the weather turns

We’ve collected 6 classic outdoor activity you can bring inside to enhance sensory development and gross and fine motor skills—even when the weather’s bad.

12 - 48 Months

Our simplest activities to do at home with your toddler

When you're short on time, try these 15 simple play ideas for spending time at home with your toddler.

12 - 48 Months

How to celebrate Halloween and maintain physical distance

Halloween will be different this year—but that doesn't mean we can't still celebrate it with our young children.

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

This powerful activity can change your child’s brain

Back-and-forth conversations with your baby have a significant impact on language development and are important for social, emotional, and cognitive growth.