12 - 48 Months

Talking About Race & Embracing Differences

“Show your child that everybody has a racial identity, we all have color, we all have a race. This is the way to actually role model equity. All races are talked about equally.”

Nicole Stamp, TV host, writer and co-founder of ByUs Box

Children’s questions about physical differences often catch us off guard. Parents worry about getting the response wrong, making the situation tense. But TV host and co-founder of ByUs Box, Nicole Stamp, says there’s a better approach.

On today’s episode with host Jessica Rolph, Nicole offers ways of thinking about these encounters from an equity perspective, ensuring everyone comes away from the interaction having had a positive experience. Equally important is the practice of building conversations about inclusion into the every day. After all, these are the conversations — which continue throughout a child’s life — that help our kids to make sense of the world.

Key Takeaways:

[1:45] We teach children to categorize from a young age by encouraging them to distinguish patterns, colors, and shapes. How does this categorization connect to the research on how toddlers are categorizing people?

[5:15] If a 2 or 3 year old walks up to somebody with a mobility device full of questions, how should a parent respond?

[6:20] Nicole explains the difference between diversity and equity.

[7:15] What does inclusion really mean?

[8:55] How can you guide a conversation with a child interested in another child with a physical difference?

[11:45] What kind of proactive steps can parents take to reinforce equity and inclusion?

[17:12] Nicole explains why being “color blind” does not help create the equitable society that we strive for.

[21:30] If a parent avoids conversations about race or other differences among people, their child is picking up on that message in non-verbal ways.

[23:33] Jessica shares her takeaways from a powerful conversation.

Script:

How Do Toddlers Categorize People?

Jessica: So for toddlers, a lot of the materials that we give as educators are helping them make sense of the world through categories, like shapes and noticing patterns and categorizing their toy by color or by, what is a fruit, what is a vegetable? How does this categorization actually connect to the research on how toddlers are categorizing people?

Nicole: That’s a great question. And the answer is that it connects very, very deeply. So children are trying to make sense of so much information as they’re encountering the world around them and the quickest way for them to do so is to categorize. So we know that when a toddler meets their first animal, it becomes… Maybe it’s a puppy and then every animal they see is a puppy for a few more months before they start to put finer points on those definitions. And that’s a really great way for toddlers to make sense of so much information, and that’s going to happen with people too.

So if you look at your family and the people that your toddler is exposed to on a daily basis, there’s some diversity already inherent in that group. Very likely, you have people of different genders in that group, people of different ages in that group, people of different body sizes are in that group. And your toddler will learn, well, all of these people, no matter what their gender, their body size, their age, whether it’s grandma or daddy or my little sister, we all love each other and we’re a family together.

But within the group of people that your toddler sees every day, there might be some kinds of diversity that aren’t there. There might not be anybody who has a mobility aid. There might not be anybody above a certain body size. There might not be anybody of certain races. And so your toddler has learned that some of these physical differences; height, beard or no beard, glasses or no glasses, they don’t really make a difference in how we interact with people. But some of these other differences; walking or wheelchair, the skin color or that skin color do seem to make a difference about who’s included in the group and who’s not included in the group.

So that will be different for each family, depending on who’s in your actual family. But what you want to do is realize that your child is going to take the identities that they haven’t had a lot of exposure to and when they encounter people from those identities, they’re going to start to generalize. So for example, if everyone your child is close with is able-bodied and they meet a person who uses a wheelchair, they’re probably going to associate the interaction they have with that person with all wheelchairs.

So that’s an opportunity for a parent to be really mindful in the kinds of interactions that their children have with different identities. So for example, let’s say, the first time your child sees a wheelchair up close, they make a comment like, “What’s that person sitting in?” And the parent gets uncomfortable and embarrassed and kind of shushes the child and pulls them away and tries to smooth over the interaction. Well, what’s happened is the child has learned, “Okay, whatever that thing was, we’re not supposed to talk about it. It must be bad. And maybe that means the person who was sitting in that wheelchair might be bad too.”

So the parent’s non-verbal communication has inadvertently shown the child we don’t feel comfortable around people like that. If a child asks a question about another person’s race and the parent finds that question uncomfortable and their body language changes and their voice changes and they cut the conversation short, the child learns the same thing. “People of that race make my parents uncomfortable.” And that’s exactly the message that we don’t want to give the child because it’s a hard message to talk about.

If that message is being communicated, it’s hard for us to undo what the child is picking up from that. Even if you say everyone is equal or you read one or two books, it’s not really going to undo that. So that’s the area where I think parents have some control in terms of thinking ahead to the kind of reactions they want to have when their children say things that are kind of surprising or maybe a little bit socially awkward. And remembering that probably the most important thing is to stay calm and keep the conversation safe, because then no matter what generalizations your child is picking up from the interaction, they’re not picking up, “This was a scary bad conversation and we shouldn’t talk to those people.”

Addressing Physical Differences with Your Child

Jessica: Can you help me paint the picture for… Let’s say this example of a two-year-old or a three-year-old walking up to somebody with a mobility device, what words should the parents say?

Nicole: I love this question. I feel like this is one of the most commonly asked questions for all of these situations. And I think a way to approach it actually that makes the burden on the parent much easier is rather than thinking about, “I have to say exactly the right thing.” I would think about, “Can I shift my framework just a little bit so that the way to react becomes a little bit more clear because I have sort of a process and a philosophy to follow?” So traditionally, when we talk about diversity, I think there are some things missing from that conversation.

Diversity sort of means bringing a rainbow of things that are different and then, “Good, we’ve done it.” And I think we can all think of situations maybe where we were part of a group that we felt like we didn’t really fit in, we were a bit different than the people around us. And in that situation, we are the diversity, but it doesn’t always feel good to be the different one. So I think there’s something missing from just diversity. If you just take a lot of different people, different races, different sexualities, different body types, different genders, different abilities, it doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone is still having a good experience.

Importance of the Principle of Equity

Nicole: I think we can move past the expectation of diversity. To me, the principle that’s really important is the principle of equity. So equity for adults can mean things like looking at representation, how many people are on the leadership team, how much money are they being paid? Is everybody… You could have a company where there is diversity among the pool of the employees, but if all the people of one color are the janitors and are being paid survival wages, you can see that that diversity is a superficial metric, that’s not making everybody’s experience equally good.

From a child’s perspective, if you have a group where most of the children come from one community and there’s a few children sprinkled in who represent different identities, you can see that while those children bring diversity to the group, they might not be having an equitable experience. It’s possible that the conversations that are happening in the group, the learning that’s happening, the way that they’re being played with or included might actually not be fair to those children and may not be equal.

Similarly to that, I think we want to talk about the feeling of inclusion. Inclusion is what it feels like when you are included. Does it feel good to be included in this way? So I think if we think about how can we bring a sense of equity and inclusion into these conversations, it becomes more clear how we can proceed.

So is your child interacting with this person in a way that’s equitable? Is it similar to the way your child is interacting with people from other groups or is this person having a different experience because they’re from an identity that’s historically marginalized? And is your child’s interaction inclusive? Does that person get to have a nice experience that day with your child’s interaction as part of the day? Or is that person being forced into a position where they have to be a teacher or an ambassador and therefore they don’t just get to have a nice restful day, they have to do this extra labor on top? I think a really good tip for parents is to think about how can I bring a sense of equity and inclusion into each of my interactions. Making it fair for the person and making sure the person is having a good experience.

Conversations and Interactions with Your Child on Differences

Jessica: I love what you’re saying here because it really links to this core desire that we have to raise kind children who are caring. There was an Atlantic Monthly article that references a study that said that more than 90% of parents say that one of their top priorities is that their children be caring. It reminds me of this photo shoot that we did with a little girl named Alora, who has a limb difference, and her mom approached me about writing a book, and we’re so excited to be creating a book about Alora, and during the photo shoot, another child came over and was very curious about Alora’s limb difference and started to have a lot of curiosity around her leg. How would you think about a framework and guiding that conversation or that interaction?

Nicole: Sure, so in the traditional kind of diversity focus, we would think, “Well, it’s good for Billy to learn about Alora’s leg because then he has been exposed to more diverse bodies,” however, if you think about it, that perspective kind of leaves Alora out in the cold a bit. So if we shift into an equity perspective, what we would want is for these two children to both have a good experience at the park that day.

So I don’t really believe in overly moderating what children say to one another, I think it’s okay for children to work out their own conversations, but if I were the parent of this child… I’ve decided to call Billy, I hope that’s okay. If I were Billy’s parents, I might think to myself, “Okay, we’ve come upon this child, and Billy has asked her questions about her body, that means that this child is put in a position of having to become an ambassador for limb differences and educate another child about limb differences.” So they’re not having an equitable relationship right now, Billy gets to be the student and Alora is forced to be the teacher.

That might be okay. Alora might be fine with that, but I wouldn’t want that to be Alora’s entire day or Alora’s entire life. If I think about later on that day, Billy might just go off on his way, but Alora might be approached by multiple other people in a day, in a week, asking questions about her body that she’s then put in a position to have to answer. So she’s not having an equitable experience to other children. And if you think about how it might make her feel that so many people she interacts with have questions about her body and that might actually be the end of the interaction, it’s probably not a very inclusive position for her. Probably doesn’t feel that good to always be questioned about her leg. So given that I don’t necessarily think we should be intervening when children have conversations, I would think about what as a parent you could do to shift the balance of that conversation.

Let’s say you were planning to spend 10 minutes at the park that day, and Billy spent seven of those 10 minutes talking to Alora about her leg. That means there’s only a couple of minutes left for playing. And that means that Alora’s day was 70% education and maybe 30% playing, and that’s not really an equitable place to put her in. As a parent, what I would do is think, “Okay, can we stay at the park a little bit longer, can we allow these children to interact in a way that goes beyond the superficial questions about Alora’s body and creates a relationship between the two children that’s equitable?”

So Alora gets to play and be a child, not just a teacher, and it’s inclusive so that Alora gets to have a nice day at the park. And then that also will give extra education to Billy because now it gives him a chance to see Alora as something more than her body, more than her limb difference, he gets to make a friend. So if I were a parent in that situation, what I would do is look ahead at my schedule and see if I could shift things around so that a bit more time can be spent to the park, and so that the balance of time that these children spend talking about someone’s difference can become smaller. If Billy could stay for an extra 20 minutes, that might mean they get a whole half hour of playing and then more of Alora’s day gets to be high quality inclusion as opposed to education that puts her on the spot to do labor.

Proactive Steps to Reinforce Equity and Inclusion

Jessica: So aside from reacting to what your child is encountering in the world, what kind of proactive steps can parents take to reinforce equity and inclusion?

Nicole: That is such a great question, and I think it’s such an important one because a lot of this stuff really does begin at home. I think because equity topics are so prominent in the news and people have a lot of emotions about them, we tend to sort of get a bit nervous and fraught about them before they happen and think, “This has gotta be a serious conversation, I can’t mess this up, I have to do this right,” and we put a lot of pressure on ourselves, which means that the conversation has this non-verbal feeling of intensity and discomfort around it that children absolutely pick up on, they really pick up on non-verbal communication from their caregivers.

Two Ways to Approach Teaching Equity

Nicole: I think there are two ways to approach teaching equity topics, number one can be an equity conversation is like a procedure, like a medical procedure that your child has to have to make them be not racist. I think that that kind of conversation is what leads into a very high pressure situation for parents where they have a lot of expectations of doing it right, they get tense and stressed and the child picks up on that tension and stress and what they come away with is, “These topics and hence those people are kind of uncomfortable and maybe I should stay away.” The other way to look at it would be to think about how we teach children how to tell time. We don’t have one serious conversation, and at the end of it, our child knows how to tell time, we expose our child to numbers, we talk about the time every day, we hang a clock on the wall and point to where the hands are pointing. It’s hundreds of very small, casual, friendly interactions that over the course of a couple of years give the child a solid grounding in how to tell time. I think we should approach equity topics the same way.

So rather than thinking, “Okay, I’m going to teach my child about racism today, we’re going to sit down, I’m going to stare them in the eye and have a serious conversation about enslavement.” If you think about it from the perspective of a child who hasn’t necessarily met very many Black people, that conversation is really intense and kind of sends a non-verbal message that Black people are really intense and kind of scary, and everyone’s very uncomfortable when Black people are in the conversation.

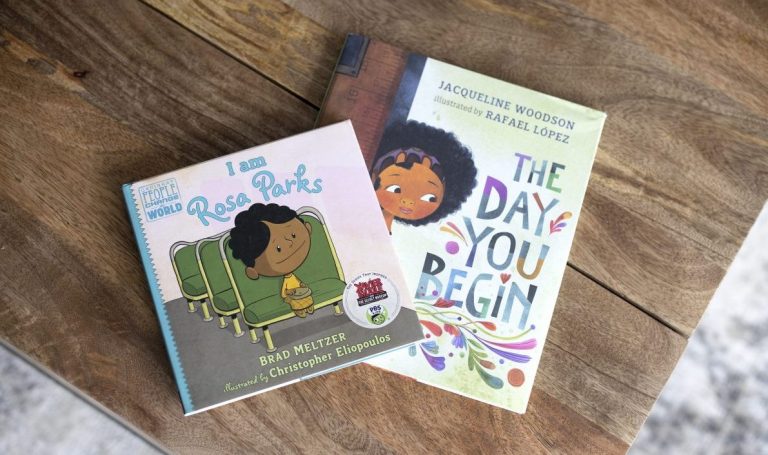

If we were to shift to the same kind of framework we use for teaching a child how to tell time, we might fill the house with books that had Black characters, we might buy a few Black dolls, we would make sure that we watch some shows with Black characters, and so our child would see Black people in all kinds of different situations, different ages, different family structures, and sort of get the ground message that Black people are like us. And that would teach your child, well Black people deserve equity because they’re like us, their families they love each other and they’re children that like to play baseball and like to have pets and all the same things that I like.

So as a parent, if you can bring a broad slate of diversity into the home through the books and the shows and the toys that you expose your child to, you’re already doing a lot of the ground work to have these conversations go in a really good way because you can just approach them casually and again and again.

Exposing Your Child to Diversity Through Books and Toys

Nicole: When you’re choosing materials, if you think again about who’s in your immediate family structure, who does your child see and who do they not have exposure to? When they don’t have exposure to a group, they’re going to start to make generalizations about that group, so it’s very important that you can bring representations of that group in that help your child create good generalizations. So that means you don’t want to only give your child books about race that talk about racism, you don’t want to only give your child books about disability that talk about a disabled person being excluded. You don’t want to only give your child books about gender or sexuality that show that children who don’t conform to gender or sexuality norms are lonely and bullied. Because what that teaches them is people like that are different, people like that are over there and have bad outcomes.

So I would look really carefully at the books and the choices of media that you present to your child and make sure that you are flooding them with positive representation of each group long before you ever get into any conversations about inequality or oppression. I think that starting from babyhood, you can give your child access to dolls, characters and shows that present to them all the different types of groups in the world, especially groups that aren’t in their own family. As they get a little bit older into the pre-school years, you can start to talk about fairness. “We treat people fairly. If we see somebody being treated unfairly here are some things we can say: ‘Please don’t be mean. Please come and play with me instead. I don’t like what you said.’” Teach your child that they can say those things.

And then as your child gets a little bit older, six, seven, eight, nine, you can start to teach about history of oppression, in a very measured way, obviously that protects children from too much violence, but because you’ve set this grounding that they’ve experienced hundreds of Black people in the books and the toys around them, when they hear about racism, when they hear about enslavement, when they hear about segregation, because they’ve been exposed to so many Black people in the media and toys and books in their house, when they hear about historical oppression of Black people, it’s not the very first time they’ve ever encountered Black characters. One of the things we suggest at the ByUs Box is that you want to flood your child with hundreds of positive representations of a group before they ever hear about trauma or violence within that group.

The truth of the world is that there are many groups that experience discrimination, racism and oppression, but we don’t have to make that the first exposure that children have to those demographics.

Why Being “Color Blind” Doesn’t Contribute to an Equitable Society

Jessica: That makes so much sense, and it’s so helpful to hear these examples. I’ve seen some of these examples in the ByUs Box, so I love hearing you come… Making them come to life here. The other thing that you talk about in ByUS Box and some of the content on engaging and discussing Blackness with kids and especially babies and young toddlers, is that naming races or saying that White and Black, it can feel uncomfortable, but that we actually need to name and acknowledge all races confidently. Can you talk a little bit more about the importance of this and why being, quote unquote, color-blind does not work in terms of creating this equitable society that we’re all going for?

Nicole: Absolutely. So in our society, we have an unspoken taboo that we try not to name powerful identities. We don’t really talk about men as much as we talk about women, we have movies and chick flicks. We don’t really talk about White people as much as we talk about people of other races, we have people and then we have Black people. And that is a really subtle thing that almost all of us do, and we don’t really think about it, but what it’s telling children is that this group of people is normal, and this group of people is other. They’re a special interest group, they’re lesser than and their concerns should be sidelined. So it’s really important for us to change that taboo. If we only talk about race when we talk about people who aren’t White, what we’re doing is we’re teaching children that White is the good normal default and that Black or Asian or Latinx is a side identity that’s not as important and should be marginalized.

Be Factual When Naming Differences

Nicole: What I would suggest instead is that we always talk about races at least in pairs. So if you’re looking at an illustration, you don’t say, “Here’s a group of children and there’s a Black child,” because what you’ve said is, “Here’s a group of normal people, and here’s a weird thing.” Instead, what I would say is, this child has brown skin and this child has pink skin, so that you’re factually naming the differences between the two children, and you’re not using race words, you’re using color words that a child is already familiar with. As your child gets a tiny bit older, maybe around two, three years old, you can say this child has brown skin and this child has pink skin, we would call this child Black and we would call this child White. So you’re always naming the two things together, which shows the child that everybody has a racial identity. It’s not that some people are other and some people are normal, it’s that we all have color, we all have race. And when you do that, what you’re doing is you’re actually role modeling equity. All races are talked about equally, it’s not that some races are mentioned as an afterthought.

So the second part of that is that our culture has a taboo against naming race, it feels almost rude or confrontational to name races. And I think it’s really important that we get past that. Racial descriptors are not insults, they’re not mean, they’re not divisive, they’re just a true thing about what a person is, the same way that you would name somebody’s gender, or the same way that you might name somebody’s height or you might name their occupation. Your race, your skin color is a part of who you are, and it has a profound effect on how you move through the world. So if we choose to pretend that color doesn’t matter, what we’re choosing to do is close our eyes to the ways in which color has a really profound effect on people’s lives. And for some of us, that’s fairly easy to do because the color of some people’s skin doesn’t have a profound effect on their life, but it really does for other people, and deciding that we’re not going to talk about that because it feels divisive is actually erasing those people’s experience.

A person who has darker skin, a person who is Black, a person who is racialized, has a different experience, they are met with experiences of discrimination and experiences of marginalization in almost every aspect of their life, and I think if we agree that racism is a problem, the next step to that is realizing that you cannot solve a problem if you are too uncomfortable to even name it. We have to be able to talk about race in order to be able to solve racism. It’s not bad to talk about race, it’s great to talk about race, and the best way to do it is casually and equally.

Babies Recognize Differences Starting at 6 Months

Jessica: It’s fascinating because it relates to the research that shows that even at six months, babies are recognizing differences in skin color, racial features, because they’re really noticing their caregivers and they’re having a preference for what their caregivers look like, and they are looking for that as they categorize the world. And so I think that as parents, the more we can understand what the research supports that your children are already noticing these differences, and then if we can lean into that in conversations like what you’ve described today, I think we can all kind of envision this world that we want our children to grow into, so…

Nicole: Yeah I absolutely agree. And the thing is, I think a lot of people sort of hope that my child is young, my child is innocent, my child doesn’t see color, and if I’m the one that starts bringing it up, I’m putting ideas into their head, or I’m bringing something to the table that wasn’t there. Research does not show that. Research shows that, as you said, children as young as six months are noticing racial differences, they’re noticing the races of people specifically that are different than those in their immediate family, and the thing is, if a parent doesn’t want to talk about race topics or disability topics or any other oppression-related topic, the child is picking that up in non-verbal ways.

They understand changes in body language, tone of voice, shortness of conversation, parent turning away, all of those messages, are going to be sent by the parent in non-verbal ways. So if we choose to avoid these topics, we are still communicating something very important to our children, which is that these are not topics that people like us should talk about, these are not people that people like us should associate with. Your child is going to pick up on that message, and draw their own conclusions from that.

Don’t Avoid Conversations on Differences and Race

Nicole: Children who don’t talk about race still notice race, all that it means is that they don’t necessarily feel safe asking, which means that they are putting together their own generalizations and drawing their own conclusions, and those conclusions could actually be harmful. So I think it’s really important to recognize that children are noticing race.

There is marked difference by age three in what race of doll a child will gravitate towards, so that means that kids by three have noticed race and have drawn conclusions about race. So as a parent, it’s really valuable to think, “Okay, either my child is going to pick up all this stuff unconsciously and draw conclusions that may not be correct, or I’m going to be a bit more mindful about this and I’m going to help my child draw good conclusions. I’m going to think about what message I want to send to my child and plan ahead a little bit so that I can send a clear positive message with my non-verbal communication because I’m comfortable with these conversations, I’m prepared for these conversations, and I can underscore the importance of these conversations and of other groups being part of our lives with the choices of media, books and toys that I bring into the house.” I would really advocate for parents rather than trying to avoid this topic and hope it doesn’t spring up, to recognize that your child is putting together a thesis about the world, race, gender, ability, sexuality, that is part of what they’re noticing. Approach it mindfully, because then you have some input.

Jessica: Now, that is such a great place to end this conversation that could go on for days with you Nicole. Thank you so much for all of the insights that you’ve shared. It’s been wonderful having you.

Nicole: Thank you so much for recognizing the importance of this issue and bringing it forward in the work that you’re doing.

2 Episode Takeaways for Parents

So much actionable information here. Let’s review some of the ways we can help guide our children to draw positive conclusions about the differences they see.

1. It’s Okay to Not Have All the Answers

You don’t need to have the answer to every single question your child will ask. What you want to do is to create a safe space in which your child feels comfortable asking questions.

Think ahead to the kind of reaction you would like to have when your child will (inevitably) say something socially awkward. Rather than coming at it from the perspective of “I have to say exactly the right thing,” think about ways in which you can create an environment that allows everyone involved to come away having a positive experience.

For example, if your child asks you “Is that person a boy or a girl?” and it feels awkward, you can respond saying “I’m not sure, because I haven’t asked them, but they’re smiling at you. Do you want to say, ‘hi’?”

2. Talking About Race is a Good Thing!

Use books, toys and media to weave inclusive conversations into your every-day. We want to name and acknowledge all races confidently. Talking about race in pairs can help: This child has brown skin and this child has pink skin. Later on, you can add: We use the words “Black” to describe this person, and “White” to describe this person.

You can find more information on how to talk to your child about these important topics on the Lovevery blog at lovevery.com.

Posted in: 12 - 48 Months, 18 - 48 Months+, Child Development, Parenting

Keep reading

18 - 48 Months+

0 - 12 Months

Lovevery’s Disability Support Service offers personalized guidance

Lovevery’s mission is right in our name—we love every baby and child. Today I’m so proud to say that we’re further realizing that mission, by better serving more families. As you know, our Play Kits are staged by a child’s age. This works for many families, but I know firsthand that it’s not ideal for … Continued

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

Lovevery for Target

Experience our new Target stage-based play essentials, as well as familiar favorites like The Play Gym and The Block Set, straight from your local Target location.

12 - 48 Months

18 - 48 Months+

0 - 12 Months

8 ways to celebrate Earth Day as a family

Earth Day is a time to celebrate nature and the environment. Teach your children how to take care of the Earth with these fun activities, crafts, and books.

12 - 48 Months

Welcome spring with these colorful, toddler-friendly DIYs

Incorporating color into these fun DIY activities stimulates your toddler's senses and deepens their learning.

12 - 48 Months

13 - 15 Months

0 - 12 Months

Celebrating Black History Month with babies and young children

Children of all races are never too young to take part in Black History Month. Here are ideas on how celebrate with your child, along with a list of books that center Black people and culture.

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

What are Montessori toys?

Some toys have characteristics that are aligned with Montessori principles. Learn what they are, why they can benefit your child, and how to introduce them.

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

You can’t balance work and parenting during Covid. That’s OK.

As we continue to adjust to new normals, some things have stayed the same: working while caring for young children during a pandemic is really hard. Here are a few ways to ease the burden.

12 - 48 Months

4 activities that expose your toddler to the wonder of color

Color brings fresh interest to STEM and art projects for your toddler. Here are 4 easy ones that use food coloring.

12 - 48 Months

6 outdoor activities you can bring inside when the weather turns

We’ve collected 6 classic outdoor activity you can bring inside to enhance sensory development and gross and fine motor skills—even when the weather’s bad.

12 - 48 Months

Our simplest activities to do at home with your toddler

When you're short on time, try these 15 simple play ideas for spending time at home with your toddler.

11 - 12 Months

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

18 - 48 Months+

Why children are so attached to their loveys (and what to do if your child loses theirs)

Loveys, also known as "transitional objects," help babies and toddlers through transitions. Learn why these blankies, stuffies, and more are important and what to do if one goes missing.

12 - 48 Months

How to celebrate Halloween and maintain physical distance

Halloween will be different this year—but that doesn't mean we can't still celebrate it with our young children.

18 - 48 Months+

Pretend Play: Outdoor Picnics

Pretend play is a great way for your child to apply their current skills and use them for different purposes.

18 - 48 Months+

Making graphs with toys

Painter's tape and small toys can turn into a great pre-math activity for young kids who love to sort and compare.

18 - 48 Months+

4 easy water dropper activities

Eye droppers are great for fine motor practice, precision, and focus, and can make an activity feel fresh and new.

18 - 48 Months+

Dot sticker play

Your child gets to work on their fine motor skills when your introduce versatile dot stickers.

18 - 48 Months+

Cracking eggs with your child

Cracking eggs takes a bit of training, but it's a great Montessori practical life activity you can begin around 3-years old.

18 - 48 Months+

Copy that monster

This game is not only good for precise drawing practice, it's also an exercise in in using descriptive words.

18 - 48 Months+

3 fun ways to get the wiggles out

Kids need to run, jump, exercise, and work out the wiggles regularly. Try these 3 simple ways to get moving.

18 - 48 Months+

Stairway math

This activity gets the wiggles out while giving your child an opportunity to practice counting and identifying numbers.

18 - 48 Months+

Fine motor threading activity

This activity is a great way for your child to strenghen fine motor skills needed for precision in their grasp, manipulation, and release.

18 - 48 Months+

7 Best Quotes About Parenthood

Here is a collection of Lovevery's favorite quotes to inspire and support you.

18 - 48 Months+

Cognitive and Emotional Benefits of Bath Time

Bathtime has many cognitive and emotional benefits beyond simply keeping your baby clean. Here's how you can help your baby get the most out of bathtime.

18 - 48 Months+

Toddlers and Their BIG Emotions

From the moment they're born, children need reassurances that a range of feelings is normal, and that emotions come and go.

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

This powerful activity can change your child’s brain

Back-and-forth conversations with your baby have a significant impact on language development and are important for social, emotional, and cognitive growth.

28 - 30 Months

18 - 48 Months+

This classic “toy” unlocks so much development

Why are blocks so foundational to childhood? Block play supports language development, STEM concepts, visual spatial skills, and more.

18 - 48 Months+

How Eye Contact Affects Your Baby’s Brain Development

A study showed that babies' brains synch with their parents’ when they learn about their social environment. Read about how eye contact plays a crucial role in developing emotional connections.

18 - 48 Months+

The Perfect Play Dough Recipe

Playdough is not only a fun and creative activity for kids, it also helps develop motor skills and finger strength. Follow our favorite homemade recipe.

18 - 48 Months+

The Huge Impact Singing Has on Your Baby’s Brain

Experts have found that singing lowers your baby's heart rate, descreases anxiety, and releases endorphins.

18 - 48 Months+

When are children ready to share?

Learn the differences between turn-taking and sharing, and when children are ready for each.

18 - 48 Months+

5 facts about toddlers to help you better understand yours

Your toddler is growing every day—physically, mentally, and emotionally. We gathered together five key facts to help you better understand your toddler and what's happening with their development right now.

18 - 48 Months+

Why do children love feeling dizzy?

Spinning around and the resulting dizziness are significant tools children use to learn about their bodies. Learn more in our blog post.