12 - 48 Months

Because it moves! How girl & boy brains differ

“Children are not a blank slate. They’re born with strengths and weaknesses, temperament and tendencies, and one of the joys of parenting is figuring out who your child is and helping your child to figure out who they want to be, and not pushing them into a pre-determined notion of what girls ought to be or what boys ought to be.”

Dr. Leonard Sax, Author of “Why Gender Matters”

“Trucks are for boys and dolls are for girls.” Our ideas around femininity and masculinity have significantly evolved in recent generations, but there is still lots of room for growth. Today’s guest argues that understanding the differences between genders — specifically, the ways in which girl brains differ from boy brains — can actually break down those gender stereotypes.

Dr. Leonard Sax is a physician and psychologist, as well as the author of Why Gender Matters: What Parents and Teachers Need to Know about the Emerging Science of Sex Differences, where he discusses key differences in how boys’ and girls’ brains are wired, including differences that show up even when the baby is in the mother’s womb.

Key Takeaways:

[2:02] How are gender differences relevant to parents of babies and toddlers?

[2:50] Girls’ brains develop much earlier than boys’.

[3:54] Leonard Sax explains differences in the visual and auditory systems among boys and girls.

[10:15] How do auditory differences play out in the home with toddlers?

[13:33] Leonard makes a connection between boys’ auditory needs and ADD diagnoses.

[14:33] The acceleration of the academic curriculum and the correlation to ADD and ADHD diagnoses.

[16:48] Leonard claims American doctors are more inclined to prescribe medication as the first resource.

[17:46] Leonard talks about varying rates of brain development among boys and girls and how parents should approach this matter.

[18:31] Every child is unique and is a mixture of masculine and feminine.

[19:20] The most important factor in raising a happy child, according to Dr. Leonard Sax.

Transcript:

I have 2 boys, and a girl. I wanted to approach my parenting from a neutral place when it comes to things that tend to have a connection to gender. Trucks for boys, princess costumes for girls. So I made an effort to expose my boys to dolls and my daughter to spiderman costumes. My kids have been interested in all of it, at different times. But I can’t help but observe my boys’ deeper affinity to things with wheels, and my daughter’s persistent interest in dolls.

My guest today argues that understanding the differences between genders — specifically, the ways in which girl brains differ from boy brains — can actually break down those gender stereotypes.

If all this talk about categorizing by gender doesn’t sit right with you, please keep in mind that this is part of our Perspective series. I invite you to give Dr. Leonard Sax a listen. He is a physician and psychologist, as well as the author of “Why Gender Matters”. In his book, he discusses some key differences in how girls’ and boys’ brains are wired. Differences that show up even while the baby is in the mother’s womb. I started by asking him how those differences are relevant to parents of babies and toddlers.

Differences in boy and girl brain development

Leonard: Okay, so there are at least three big domains of hardwired difference that parents of young children, babies, toddlers need to understand. One is in the pace of brain development. When we have all kinds of longitudinal studies now for the National Institutes of Health from Harvard, from UCLA, where they’ve taken large groups of kids, followed these kids from birth through childhood into adolescence and into adulthood now, because these studies have been going on for more than 20 years, and watching how the brain develops, and a very robust finding that all the centers agree on is that girls develop faster than boys do. That is true, whether you’re black or white, urban, suburban or rural, affluent or low income, it is robust internationally, girls develop faster than boys do, and it’s quite a big difference, it’s not a small difference.

So for example, girls reach the halfway point in brain development at about 11 years of age, boys by about 15 years of age. That’s more than two standard deviations of difference separating the average girl in the average boy. And so girls reach full maturity brain development by about 22 years of age, boys not until about 30 years of age, which explains a lot, if you think about it. And these differences are very apparent at ages one, two, and three, if you look for them. But again, most parents have never heard this research and most mainstream media don’t discuss it.

One of the motivations I had in writing this book was to share this research with parents so that you don’t have to read the Journal of Neuroscience to be aware of these findings. Although, in my book, I do provide all of the citations for parents who want to look them up and read the original research, which I always encourage parents to do. So that’s one big difference. Other big differences have to do with the visual system and the auditory system.

Differences in the visual system

So let’s talk about sex differences in the visual system. So this work actually emerged from studies in which researchers gave little kids a choice of playing with a colorful doll or a dull, gray truck. There are about a dozen such studies published over the last 50 years, and there’s variations in terms of what choice they give the kids, but basically, what happens when you give a two-year-old or a three-year-old a choice of playing with a stereotypically girl toy like the Barbie doll versus a stereotypically boy toy like a dull, gray truck? And researchers at all times, and there’s been very little change over time in what researchers find, they find that the girls slightly prefer to play with dolls rather than trucks, but it’s not a huge difference. Boys at every age greatly preferred to play with the dull, gray truck rather than with the colorful doll.

And I first encountered some of these studies 40 years ago when I was earning my Doctorate in Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, and the professor of developmental psychology leading the seminar, Justin Humphrey, the late Justin Humphrey, explained to us that this is because of the social construction of gender, that girls choose dolls and boys choose trucks because that’s what we’ve taught them to do, that we teach girls that girls are supposed to play with dolls, we teach boys that boys are supposed to play with trucks. And I didn’t question that. I don’t know of anyone who did back in the 1980s. Gerianne Alexander, who was then at Yale, was the first to come up with the idea, 18 years ago, of giving juvenile monkeys the same choice. What happens when you give little monkeys, literally, monkeys, a choice of playing with a dull, gray truck or colorful doll? And you find the same thing you find in humans, which is that the female monkey, slightly, but not significantly, prefers to play with the doll rather than the truck. You find that the juvenile male monkey greatly prefers to play with the dull, gray truck rather than the colorful doll.

Now, you could try to invoke the social construction of gender to explain this finding, you’d have to assert that the monkey in authority is saying something like, “Now, son, I don’t want to see you playing with a doll.” But this doesn’t happen. The researchers who have done the work say that the monkey in authority is paying no attention to the choices made by the juveniles and the results are the same, whether you conduct the study in the colony or in isolation. You cannot possibly invoke the social construction of gender to explain the finding that juvenile male monkeys greatly prefer to play with a dull, gray truck rather than a colorful doll.

So Gerianne Alexander was the first to document this finding in a non-human species, and also the first to provide an explanation. And her explanation or her hypothesis, as it was 18 years ago, to understand her hypothesis, you have to know something about how the visual system is wired in all higher primates: Human, chimpanzee, and monkey. You remember learning about the rods and cones in high school, the cells at the back of the retina, they convert light into a signal the brain can understand. You recall that the rods are black and white sensitive and they’re all through the retina, the cones come in three varieties: Red, green, and blue, and they’re concentrated at the center of the field of vision. You might also recall from your high school biology, the next layer in the retina, which are the ganglion cells, and they take that information of the rods and the cones and begin to process it.

It’s more than 30 years now since Leslie Ungerleider and her colleagues demonstrated that there are two visual systems in the brains of all higher primates. One visual system arises from the big ganglion cells and it’s looking for speed and direction and change in direction. It’s the so-called “where” visual system, because it’s answering the question where, where is it going? How fast is it moving? The other visual system arises from the little ganglion cells, and it’s answering the question, What? What is its color? What is its texture? So that’s old stuff in neuroscience that’s been established doctrine for 30 years. Professor Alexander was the first to argue that the where system, resources in the where system predominate in males, whereas resources in the what system predominate in females. And when she made that argument 18 years ago, it was a hypothesis, but over the last 18 years, we’ve gotten a great deal of research that provides very strong support for her hypothesis.

So what does Gerianne Alexander’s answer to the question of why the juvenile male, whether human, chimpanzee or monkey, greatly prefers to play with a dull, gray truck rather than a colorful doll? The answer is because it moves, it’s got wheels. It goes, “Kaboom.”

Boys at two to three years of age will typically prefer toys that move, toys that go places, that you can roll and throw and move. Girls will, on average, prefer toys that have a more interesting color detail and texture. Notice that this has nothing to do with nurturing or parenting, this has to do with hardwired differences in the individual system.

Auditory differences

Jessica: Oh, this is fascinating. And you talk in your book about auditory differences, and you cite research demonstrating that the average girl is more sensitive to mid-waved sounds compared with the average boy, and you point out that the father who doesn’t understand this is more likely to have a daughter who says that their father is always shouting at her. And so this lack of awareness of these hardwired male-female differences can really create some problems for the family. Can you talk about how this might play out in the home with toddlers?

Leonard: Yeah. So we humans differ from one another in how we experience sounds, and older people have hearing that is less sensitive than younger people, on average. Boys and men have hearing that is less sensitive than girls and women at each age.

In Why Gender Matters, I share many studies going back 50 years to a study by Dan McGinnis, Stanford, as well as many more recent studies showing that across the frequency spectrum, from low pitch to high pitch, girls are about eight decibels more sensitive. In other words, when kids match the loudness of sounds, you need to turn it up about eight decibels for the boys to hear it as well as the girls hear it, and this is clearly present among young children, children five years of age and under, as well as older children, this difference is robust throughout life at every age. Girls have more sensitive hearing than boys do, on average.

Speak louder for boys

What does this mean? Well, there’s a couple of very practical implications that I’ve encountered in my own medical practice. One, again, is that parent who has both a daughter and a son is very likely to think their son is ignoring them or that their son has some kind of hearing problem because she’ll say, “I speak in exactly the same way to my daughter and my son and my daughter hears me and my son doesn’t, so he’s ignoring me.” Or my son doesn’t, and so he must have something wrong with his hearing. Well, no, actually, it could just be that he’s a boy. You have to speak a little bit more loudly, so 8 decibels more loudly. It’s about three notches on a typical stereo. So right now, I’m speaking at about 52 decibels, if you’re 10 feet away from me. This is about 52 decibels. And this is about 60 decibels. It’s a little bit louder. It’s not a lot louder, it’s a little bit louder. And parents, over the last 30 years, have been telling me, “It really makes a difference.” And I say 30 years because this is one difference I first encountered when I was earning my PhD in Psychology.

And it really struck me at the time, “Why don’t more people talk about this?” ‘Cause I think this is something every parent should know, that you need to speak a little more loudly in order for your son to hear you. It’s immensely relevant and practical. And again, I have found, as a clinician, many, many boys who are getting diagnosed with ADD, when in fact they’re just not hearing the teacher as well as their female classmate is. Now, that’s not the whole story, there’s a lot more to the ADD story, but there are certainly some boys who have been misdiagnosed, when in fact the real problem was that the teacher was too soft-spoken.

ADD diagnosis

Jessica: So is that one of the main reasons why you think so many more boys than girls have been diagnosed with ADD?

Leonard: Actually not. It’s a small part of the story. So we know so much about Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. It is the most common psychiatric diagnosis among American children, and I have been reading this literature now for 40 years since I was a graduate student in Psychology 40 years ago. So 40 years ago, about 1% of American boys had been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Today that figure is 20%, so that’s a 20-fold increase, 20 times as many boys per capita now being diagnosed with ADHD compared with 40 years ago. Why did that happen? Why did ADHD go from being an unusual diagnosis to an extremely common diagnosis? And again, there are multiple factors in play. But a very big one was the acceleration of the early elementary curriculum. 40 years ago, even 30 years ago, kindergarten and pre-K was about playing Duck Duck Goose and singing in rounds, and going on a field trip to the park to splashing a pond and chasing after tadpoles. That’s what three and four-year-olds did 40 years ago. But today, when you go to a typical American nursery school or pre-K, you will find that there’s now an academic focus, and this has trickled down into how we work with three-year-olds. And they have the alphabet up on the wall, and kids are learning the alphabet at three and four years of age.

Attention spans in boys vs girls

Now, the brain research tells us this is wildly inappropriate, that the language areas of the boy’s brain is way behind, they’re not developmentally appropriate. At… A three and four-year-old boy is not ready to learn that, but he’s in a classroom where everyone is learning it. And the attention span is much different. The average three-year-old girl has an attention span that’s about twice as long as the average three-year-old boy. So she can actually sit for a few minutes and learn the letters of the alphabet, and most three-year-old boys just can’t. And the teacher will report to the parent, “You know, Jason’s really struggling. He’s not paying attention. He’s rolling around and doodling and throwing things during quiet time, story time, when he’s supposed to be paying attention.” And the parent’s like, “Wow, he’s not paying attention. He must have ADHD.” And you go to the doctor, and in the United States and in no other country with the possible exception of Canada, when you take your three-year-old to an American doctor and say, “The teacher said that my son isn’t paying attention, and here are his Conners Scales and he’s off the chart indeed, and not paying attention, not concentrating, not focusing at three years of age, in the United States, it is very common to find doctors who will say, “Well, let’s try Adderall or Vyvanse, and see if it helps.”

And one reason for that is that American doctors are very likely to use medication as a first resort, whereas outside of North America, it is the last resort. So the idea of diagnosing a three-year-old with ADHD is just really questionable, especially when you’re saying a three-year-old boy won’t sit still and be quiet. It is very common to find three-year-old boys who don’t sit still and be quiet. That’s not a sign of ADHD, it’s a sign of being a three-year-old boy. We are pathologizing boyhood, and that’s a major theme of my book, “Boys Adrift,” that boys doing things that boys have always done, three-year-old boys running around and not paying attention, is now considered a sign of ADHD, whereas in fact, it’s normal boy behavior.

Jessica: Fascinating, and so helpful for us parents to be able to understand our children and have just a little bit more security in this data. So now the gender-expansive and non-binary identities are just becoming a lot more common, additional research and funding is going into understanding gender, how might this impact our perception of gender?

Leonard: Alright, so suppose your three-year-old son says, “I’m not a boy, I’m a girl.” What is best practice? What should parents do?

Well, first of all, you want to get a handle on what he means, and researchers who… And again, we’ve had lots of research on this. This is not a new phenomenon, there have always been three-year-old boys who say they are girls. And a group in Toronto has been studying such boys for almost 40 years, and they followed them. So that boy who’s three years old in 1990, is now in his 30s. What happens long-term with a three-year-old boy who says he’s a girl? What they found is that when a three-year-old boy says he’s a girl, what he often means is that he doesn’t like playing with guns, he doesn’t like whacking other kids, he’d much rather sit and play with a doll. And he sees girls playing with dolls and boys playing with guns, and he figures, “I must be a girl.”

What happens with that boy down the road? What is the most common outcome 20 years later? Well, the single most common outcome the Toronto researchers found, is that that boy grows up to be a gay man. He’s not a woman, he doesn’t want to be a woman, he is a gay man, and he still much prefers dolls over trucks. How to distinguish between the boy who is going to be a gay man from the boy who is truly transgender, that distinction cannot be made accurately with a three-year-old child, cannot be, and we have, again, so much research on this point. To understand whether this kid is gonna grow up to be a gay man, a straight man… Incidentally, I as a child, much preferred ballet and macrame to guns or trucks. So I was a gender atypical boy and I actually grew up to be a straight man. And this again is not unusual, that was the second most common outcome. Most common outcome of the three-year-old boy who says he’s a girl is he grows up to be a gay man, second most common outcome is he grows up to be a straight man.

It was actually quite rare, about 2% of three-year-old boys who said that they were girls, in the Toronto study, persistent, meaning that 15 years later, they still said that they were in fact female. And we have many studies, and I cite quite a few of them in the new edition of “Why Gender Matters”. To make that distinction between transgender versus homosexual versus straight, you have to know the child’s sexual orientation, but it is not possible to know the sexual orientation of a child before the onset of puberty.

The point I’m trying to make in “Why Gender Matters” is that every child’s unique, every child is a mix of masculine and feminine, and we have to help each child to find the right blend of masculine and feminine for them, that children are not a blank slate, that they are born with strengths and weaknesses, temperament and tendencies, and one of the joys of parenting is figuring out who your child is and helping your child to figure out who they want to be, and not pushing them into a predetermined notion of what girls ought to be or what boys ought to be.

Parent-child relationship is key

Jessica: One of your parenting presentations addresses the one thing that parents can do to greatly improve the odds so their child would grow up to be happy and healthy, would you be willing to share that one thing with us here in closing?

Leonard: Sure, absolutely, that one thing is to prioritize the family. And again, we have… I devote two chapters in my book, “The Collapse of Parenting,” to reviewing every relevant longitudinal cohort study that bears on this question. Longitudinal cohort study means you recruit a bunch of kids at birth, and then you follow them for 15, 20, 30, 35, 38 years. So these studies are just a huge investment of energy over 40 years time. And what you find is that the parent-child relationship is the key to everything. Now that may seem banal but many American parents seem to have forgotten it, and you will find parents of two year-olds who are driving their kid from one play date to another, acting as if having a lot of two-year-old friends is the most important thing for their two-year-old. It’s not.

The most important thing for your two-year-old is to have a strong parent-child relationship that is built around having fun together. So my advice, cancel the play date, make a family date instead, take more time to do fun stuff with your toddler, with your two-year-old, don’t worry so much about the play dates that can come later, the parent-child relationship is fundamental.

Jessica: You’ve written such a fascinating book and I can’t wait to have everyone learn more from your books. So, thank you, Leonard.

Leonard: Thanks so much for inviting me.

You can find more tips on Lovevery’s blog, Here with you.

Posted in: 12 - 48 Months, 18 - 48 Months+, Gender, Cognitive Development, Child Development, Behavior

Keep reading

18 - 48 Months+

0 - 12 Months

Lovevery’s Disability Support Service offers personalized guidance

Lovevery’s mission is right in our name—we love every baby and child. Today I’m so proud to say that we’re further realizing that mission, by better serving more families. As you know, our Play Kits are staged by a child’s age. This works for many families, but I know firsthand that it’s not ideal for … Continued

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

Lovevery for Target

Experience our new Target stage-based play essentials, as well as familiar favorites like The Play Gym and The Block Set, straight from your local Target location.

12 - 48 Months

18 - 48 Months+

0 - 12 Months

8 ways to celebrate Earth Day as a family

Earth Day is a time to celebrate nature and the environment. Teach your children how to take care of the Earth with these fun activities, crafts, and books.

12 - 48 Months

Welcome spring with these colorful, toddler-friendly DIYs

Incorporating color into these fun DIY activities stimulates your toddler's senses and deepens their learning.

12 - 48 Months

13 - 15 Months

0 - 12 Months

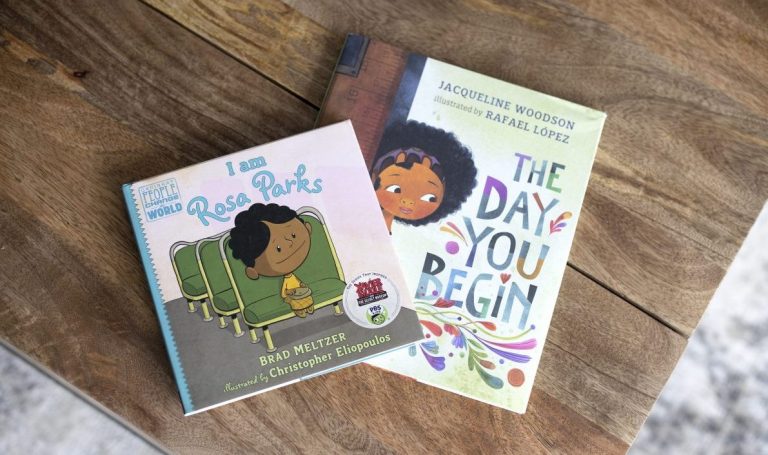

Celebrating Black History Month with babies and young children

Children of all races are never too young to take part in Black History Month. Here are ideas on how celebrate with your child, along with a list of books that center Black people and culture.

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

What are Montessori toys?

Some toys have characteristics that are aligned with Montessori principles. Learn what they are, why they can benefit your child, and how to introduce them.

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

You can’t balance work and parenting during Covid. That’s OK.

As we continue to adjust to new normals, some things have stayed the same: working while caring for young children during a pandemic is really hard. Here are a few ways to ease the burden.

12 - 48 Months

4 activities that expose your toddler to the wonder of color

Color brings fresh interest to STEM and art projects for your toddler. Here are 4 easy ones that use food coloring.

12 - 48 Months

6 outdoor activities you can bring inside when the weather turns

We’ve collected 6 classic outdoor activity you can bring inside to enhance sensory development and gross and fine motor skills—even when the weather’s bad.

12 - 48 Months

Our simplest activities to do at home with your toddler

When you're short on time, try these 15 simple play ideas for spending time at home with your toddler.

11 - 12 Months

13 - 15 Months

16 - 18 Months

18 - 48 Months+

Why children are so attached to their loveys (and what to do if your child loses theirs)

Loveys, also known as "transitional objects," help babies and toddlers through transitions. Learn why these blankies, stuffies, and more are important and what to do if one goes missing.

12 - 48 Months

How to celebrate Halloween and maintain physical distance

Halloween will be different this year—but that doesn't mean we can't still celebrate it with our young children.

18 - 48 Months+

Pretend Play: Outdoor Picnics

Pretend play is a great way for your child to apply their current skills and use them for different purposes.

18 - 48 Months+

Making graphs with toys

Painter's tape and small toys can turn into a great pre-math activity for young kids who love to sort and compare.

18 - 48 Months+

4 easy water dropper activities

Eye droppers are great for fine motor practice, precision, and focus, and can make an activity feel fresh and new.

18 - 48 Months+

Dot sticker play

Your child gets to work on their fine motor skills when your introduce versatile dot stickers.

18 - 48 Months+

Cracking eggs with your child

Cracking eggs takes a bit of training, but it's a great Montessori practical life activity you can begin around 3-years old.

18 - 48 Months+

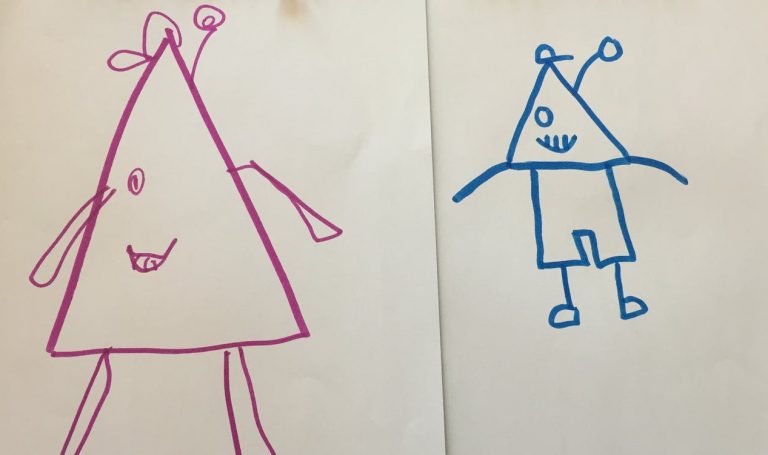

Copy that monster

This game is not only good for precise drawing practice, it's also an exercise in in using descriptive words.

18 - 48 Months+

3 fun ways to get the wiggles out

Kids need to run, jump, exercise, and work out the wiggles regularly. Try these 3 simple ways to get moving.

18 - 48 Months+

Stairway math

This activity gets the wiggles out while giving your child an opportunity to practice counting and identifying numbers.

18 - 48 Months+

Fine motor threading activity

This activity is a great way for your child to strenghen fine motor skills needed for precision in their grasp, manipulation, and release.

18 - 48 Months+

7 Best Quotes About Parenthood

Here is a collection of Lovevery's favorite quotes to inspire and support you.

18 - 48 Months+

Cognitive and Emotional Benefits of Bath Time

Bathtime has many cognitive and emotional benefits beyond simply keeping your baby clean. Here's how you can help your baby get the most out of bathtime.

18 - 48 Months+

Toddlers and Their BIG Emotions

From the moment they're born, children need reassurances that a range of feelings is normal, and that emotions come and go.

12 - 48 Months

0 - 12 Months

This powerful activity can change your child’s brain

Back-and-forth conversations with your baby have a significant impact on language development and are important for social, emotional, and cognitive growth.

28 - 30 Months

18 - 48 Months+

This classic “toy” unlocks so much development

Why are blocks so foundational to childhood? Block play supports language development, STEM concepts, visual spatial skills, and more.

18 - 48 Months+

How Eye Contact Affects Your Baby’s Brain Development

A study showed that babies' brains synch with their parents’ when they learn about their social environment. Read about how eye contact plays a crucial role in developing emotional connections.

18 - 48 Months+

The Perfect Play Dough Recipe

Playdough is not only a fun and creative activity for kids, it also helps develop motor skills and finger strength. Follow our favorite homemade recipe.

18 - 48 Months+

The Huge Impact Singing Has on Your Baby’s Brain

Experts have found that singing lowers your baby's heart rate, descreases anxiety, and releases endorphins.

18 - 48 Months+

When are children ready to share?

Learn the differences between turn-taking and sharing, and when children are ready for each.

18 - 48 Months+

5 facts about toddlers to help you better understand yours

Your toddler is growing every day—physically, mentally, and emotionally. We gathered together five key facts to help you better understand your toddler and what's happening with their development right now.

18 - 48 Months+

Why do children love feeling dizzy?

Spinning around and the resulting dizziness are significant tools children use to learn about their bodies. Learn more in our blog post.